“Most of the writings about the history of clothes – or, in fact, about the history of footwear – never linger on that particular feature known as the heel. We decided to spend some time on this topic, in order to make our study as complete as possible.

Browsing the books written about footwear, one would learn that heels first appeared in 15th century, and then gradually became a commonly accepted part of the shoe.

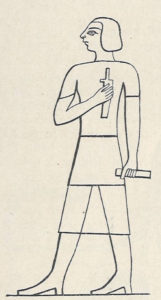

Having said that, we can’t comfortably state that heels were never used before that date. Even if the examples of heeled shoes in the olden days don’t abound, documents dating back to ancient Egypt definitely confirm that heels were used in that culture. For more evidence, just go back to the section of our book in which we wrote about a certain historical character who used to wear heeled boots.  The author who originally wrote about him identifies the man as an artisan, which suggests that in those days heels were mostly used in working shoes or to walk on muddy ground. Then again, even Indians used heeled shoes, as we mentioned in the monograph dedicated to their culture. Here’s a passage from it: “In his Description des Indes, Arien states that rich Indians used to wear well-tanned white leather shoes, equipped with high heels to increase their height. Historians believe that these shoes date back to 1250 B.C.”. Today, many believe that the heel’s invention was born out of necessity, as it often happens with human creations.

The author who originally wrote about him identifies the man as an artisan, which suggests that in those days heels were mostly used in working shoes or to walk on muddy ground. Then again, even Indians used heeled shoes, as we mentioned in the monograph dedicated to their culture. Here’s a passage from it: “In his Description des Indes, Arien states that rich Indians used to wear well-tanned white leather shoes, equipped with high heels to increase their height. Historians believe that these shoes date back to 1250 B.C.”. Today, many believe that the heel’s invention was born out of necessity, as it often happens with human creations.

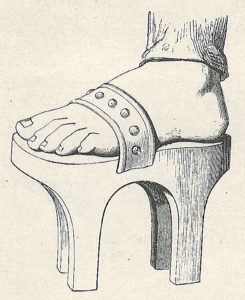

According to some writers, the heeled shoe was invented by Persians, who used to place wooden blocks beneath the sole of sandals in order to isolate their feet from the scorching sand. In the beginning, these heels were 4 centimeters high, but in time women started to use higher heels, in certain cases up to a whopping 36 centimeters. Men, on the other hand, kept using the original, and definitely more practical, height.

who used to place wooden blocks beneath the sole of sandals in order to isolate their feet from the scorching sand. In the beginning, these heels were 4 centimeters high, but in time women started to use higher heels, in certain cases up to a whopping 36 centimeters. Men, on the other hand, kept using the original, and definitely more practical, height.

The writer informing us about all of this somehow forgot to mention that, in order to feature such a heel, the shoes had to be equipped with wedges of the same height under their front part. Of course we already know about the stilted-slipper, whose cork wedge greatly increased the height of those wearing it. We also know about Turkish women wearing wooden clogs, whose upper part consisted of a simple leather band. However, these wedges can’t be considered as proper heels – in fact they have nothing in common with the high heels worn by Louis XV of France or the heeled boots used during the 15th century.

After the Persians, Venetian women too accepted the use of heels.

The shoes they called chopines featured a variety of ornaments sprung out of the shoemakers’ creativity – sometimes they were inlaid with nacre, other times they were painted. The height of their heels stated the social rank of those wearing them, and beacause of this, noblewomen often wore them so high that they were virtually unable to walk.

Beginning from the period in which heels were widely accepted, fashion started determining their height. But fashion itself was influenced by the whims of the rich and noble – it’s often told that during the reign of Louis XIV, queen Maria Theresa tried to compensate for her short height wearing exaggeratedly high heels.

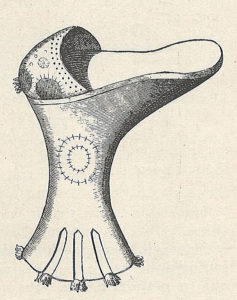

The Louis XV heel, still fashionable in our days, stood out for its elegance since the moment it was designed. Given its name, one could easily think that it was conceived under the reign of Louis XV, but that wouldn’t be right – it was just a personal preference of this king known for his effeminate aesthetic taste.

The Louis XV heel was actually invented by Leonardo da Vinci (whom, aside from being a great painter, was an architect, an engineer and a musician) towards the end of the 15th century. Heels were particularly useful to walk on the rutty roads of the time, but they subsequently became higher and higher, so dangerous that the lawmakers tried to ban them. In order to reconcile convenience and fashion, Leonardo da Vinci invented a kind of heel that was enthusiastically adopted by the following generations.

Quoting: J-B. YERNAUX

“LA CHAUSSURE A TRAVERS LES AGES” (first edition, 1929)

Ed. A. BIELEVELD, Bruxelles

Photographic and Bibliographic research by: Barbara Placidi

facebook

facebook  instagram

instagram  x

x